Brian Froggatt represented New Zealand in Paralympics in both Para athletics and Para powerlifting. At 61, he’s still winning titles and challenging his body to go beyond its limits. Margot Butcher tells his remarkable story.

Picking up the newspaper, the 12-year-old Dargaville boy was about to experience a seminal moment. Inside, an article about Charles Atlas caught his eye. Atlas was an American bodybuilding guru whose story of transforming himself from “scrawny weakling“ to strongman with a Herculean physique launched his global self-improvement brand.

“Just reading about it inspired me to start doing physical exercise,“ Brian Froggatt recollects. “I was always very shy, and I wanted to improve myself.“

When he found out a friend’s father had weights in his basement, he asked if he could use them. “He showed me a few basic exercises and I haven’t stopped.“

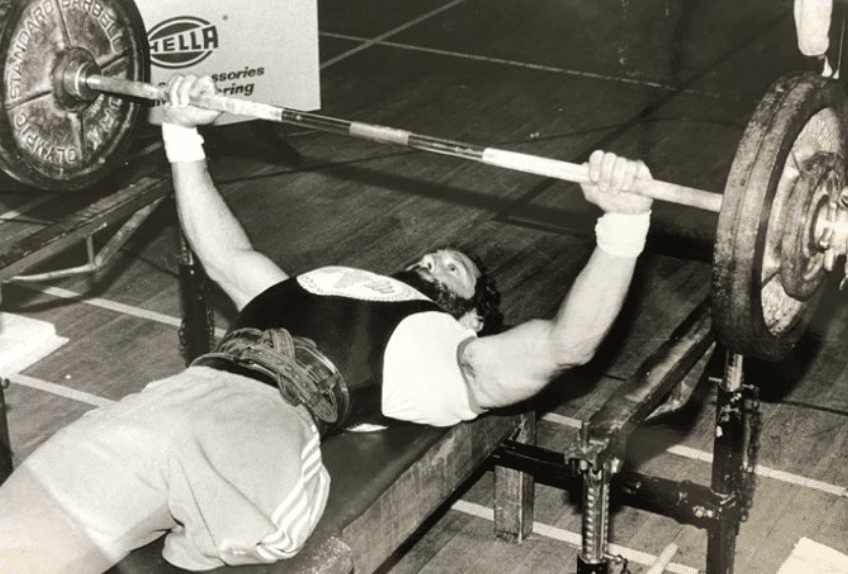

Fast forward 49 years and 61-year-old Froggatt walks into an eye-catching, blue wooden building near the Dargaville riverfront. It used to be a Masonic lodge, but for the past 28 years it’s been Brian’s Gym & Fitness Centre. He owns and runs it with wife Karen. They share a passion for powerlifting – both have won gold medals at world level in the bench press (Brian twice). They met in the gym, and now they have four grandchildren.

When Froggatt started, there weren’t any commercial gyms in Dargaville – gyms weren’t really a “thing“ back then, unless you were a boxer. Cold concrete basements and smelly garages were where you pressed iron, which is why 44kg of weights occasionally dented his friend’s father’s floor. Lucky it was a dirt floor!

Eventually he would buy more weights so he could begin training other kids in the neighbourhood in that basement. He became a fitter and turner by trade which brought the advantage of being able to make gym equipment on the weekend. Once he got his own house, he trained people there: “Up to 35 people, part-time, which made it a fairly busy garage“. That was 1985.

Next step: opening Dargaville’s first “proper“ gym. Froggatt himself was one of the town’s most accomplished sportspeople by then. He represented New Zealand at the Arnhem 1980 Paralympic Games in Para athletics and again in Barcelona 1992 Paralympics in Para powerlifting, setting a New Zealand Para powerlifting record. He’d been keen to lift in 1980, too, but the powerlifting preliminaries clashed with his long jump.

“I went along to watch the lifting later that day and was really disappointed to realise I would have easily won the bronze medal. Meanwhile, I was fifth in the pentathlon. I loved Para athletics, but I was never in the same league as the top guys. It was a missed opportunity.“

“As a child I was told I couldn’t ride a bicycle or run. Which made me determined to do both! A friend helped me to learn to balance on a bike and with the aid of toe clips on one pedal I was off! At the Paralympics in Arnhem I watched above knee amputees run the 100 metres race and immediately thought – if they can do it, I can do it! I noticed that some of the runners had an elastic strap over the prosthetic knee joint to help them run, so when I returned home I screwed a thick elastic strap over my knee joint and learnt to run! I had always enjoyed swimming, so once I had mastered running & cycling it was natural for me to enter triathlons! Eventually competing in about 10 triathlons during the eighties.”

He may not have won a medal but Froggatt describes representing New Zealand at the Paralympics – as our 33rd Paralympian – as “the ultimate“ experience.

But it was the result of endless hard work. At his peak, he would train three times a day, six days a week. Pentathlete. Powerlifter. Marathon runner. The common ingredient? “I like to set myself goals, and I’m stubborn.“ At the New York City Marathon in 1985, he broke the record for the world’s fastest time by an above knee amputee, then beat his own record the following year. His list of national and international Para powerlifting records, titles and achievements runs off the page. Froggatt has held New Zealand Para powerlifting records in four different weight classes and, now that he competes at Masters level, he also holds able-bodied New Zealand records in two weight classes.

He started competing in able-bodied powerlifting back in 1977, a full year before he discovered he could also compete regionally at what were then called the Disability Games (in Kawerau, Bay of Plenty). One year, watching the New York City Marathon on TV in the early hours of a Sunday, he spotted an American amputee running. It was Dick Traum, who, in 1976, had become the first person in the world to complete a marathon with a prosthetic leg. “I managed to get in touch with him and he invited me over.“

Froggatt also ran with a prosthetic, having been born with no femur in an underdeveloped left leg – amputated when he was three. Being a hip disarticulation amputee meant running, with a hop and a skip, on a heavy, 7kg prosthesis: the lighter flex-foot he would later adopt hadn’t come along yet.

“It was all willpower at the end, as anyone who runs a marathon will tell you,“ he says. “I lost a bit of skin from chafing, but I’ve got a pretty high pain threshold. What annoyed me was I hit the wall at the 20-mile mark. I wasn’t satisfied with my time and realized I hadn’t done enough mileage. So I went back the next year and reduced it by 18 minutes, to four hours 54 minutes, and that record stood for 21 years.“

A reporter from Radio Northland had gone to New York with him. “When we got back to Dargaville, we drove through town and there was nobody in the streets. I couldn’t figure it out. Then he took me to the back entrance of the Town Hall. I said, ‘What’s this all about?“ and he said, ‘Just come in for a minute.’ He led me onto the stage, and here was the Town Hall packed out.“

Emotion cracks his voice even now as he recounts it. But it still didn’t compare to being New Zealand’s 33rd Paralympian. “That really meant a hell of a lot to me,“ he says.

It meant a hell of a lot to Dargaville, too. When he was selected for the Paralympics, “People were donating money all the time to help me get there. It was getting very embarrassing but it was hugely appreciated. I would walk down the street and people would just hand me money!“

It took arthritis, a knee replacement and two shoulder replacements to stop him running, but he still competes in bench press championships, and trains in the squats and deadlifts — a feat of explosive power while balancing on one leg.

“It’s terribly slow and frustrating starting again every time after surgery, but I just like the challenge. I like to set myself goals. I’ve competed in a few able-bodied world champs at Masters level now, and my best place so far is fourth. There’s always a dream of improving.“

Story created by Storyation in partnership with Paralympics New Zealand.