Story written by Ashley Stanley for LockerRoom.

In 1984, Para alpine skier Viv Gapes became New Zealand’s first Winter Paralympian to win a medal – and to win gold. Today, she still loves adventure, Ashley Stanley discovers, but on a different course.

The Nakasendo trail in Japan is an ancient set of paths connecting Tokyo and Kyoto.

It was one of five routes used by authoritative figures, like shogun, to control territories during the early 1600’s.

Nowadays people can walk parts of the trail and stay in small towns tucked away along the 530km journey in the central mountain ranges.

Viv Gapes was one of the thousands of people last year exploring the track – in the rain – in a week-long adventure during the Rugby World Cup.

The experience was “pretty amazing“ for Gapes, but she’s no stranger to amazing achievements. The partially-sighted alpine skier also happens to be New Zealand’s first Paralympic Winter Games medallist – and first gold medallist.

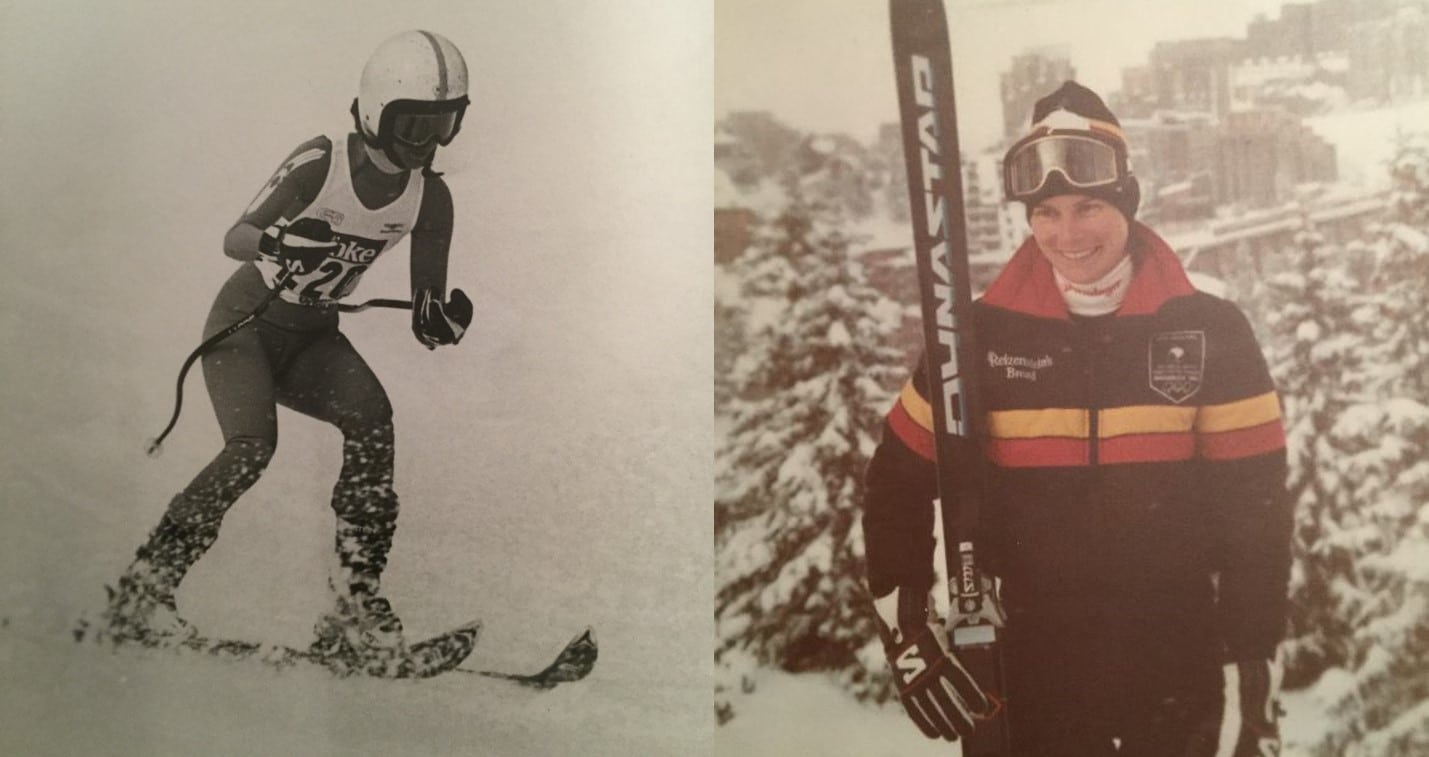

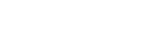

Back at the 1984 Paralympic Winter Games in Innsbruk, Austria, the then Viv Martin was New Zealand Paralympian #45, who brought home gold and two silver medals from the ski slopes.

Today Gapes is an avid walker, despite being born with ocular toxoplasmosis, an infection that caused scar tissue to cover her retinas, leaving her with very blurred vision. Gapes isn’t one to let the haziness limit her though.

“I have no central vision, so my eyes wriggle all the time. But I think they’re very clever because they have learned to adapt to the fact that if they were still, I wouldn’t see anything,“ laughs Gapes, who turns 61 next week.

“I have good peripheral vision which is a blessing, so I can walk around independently. I can’t drive, I can’t read fine print and I often buy weird things in the supermarket, but you know, you learn as you get through life.

“I’ve always thought I was lucky that I hadn’t lost [my sight] later because I think that would’ve been harder. You just have to be positive.“

That optimistic outlook on life is how Gapes began skiing while studying for her Bachelor of Arts at the University of Otago.

“This amazing woman named Gilly Hall started skiing for disabled people in New Zealand,“ says Gapes.

McDonald went through the physical education school searching for students to help her cause and managed to find people with disabilities through the university roll.

“I just said ‘yeah, I would love to try that’. I’m always keen to try something new and that’s how I learnt how to ski,“ Gapes says. “I would just go and ski whenever I could. I was addicted. It’s an addictive sport – the speed, being outdoors, the snow, and the camaraderie.“

Gapes turned out to be quite good, and asked if she had ever thought about joining a ski team. Good was an understatement.

She skied away with a gold medal in the giant slalom B2 event, and silver in both the B2 downhill and alpine combination at the 1984 Paralympic Games. It was the first time New Zealand had female athletes competing at a Winter Paralympics.

Gapes would then repeat that triple medal haul two years later at the alpine skiing world championships in Sweden.

She says those moments were “really exciting, but pretty scary“ at the same time.

“When you’re standing at the top of the race course listening to get a good start and then trying to go as fast as you can when it’s really slippery – while also trying to memorise the course – it’s hard work,“ she says.

“But those times were also really exhilarating. I met loads of people who have all sorts of physical challenges who just live really great lives and get on with them.“

She credits the training conditions in New Zealand for her international success.

“The team would go on a training week and everything would be snowed under,“ says Gapes, who grew up on a farm in Central Otago.

“The weather would be shocking and no one would be able to see anyway so it’s really good for your feel – your feeling of the slope and softness in your knees, and all of the stuff you have to know when you can’t see where you’re going.“

Gapes used these experiences when competing with her sighted guide, Mike Curzon, at the Paralympics. He was also the New Zealand team’s physiotherapist.

“He skied right in front of me. They’re not allowed to touch you, so you have to work together,“ she says. “We would ski together a lot, and figure out communication systems, like tapping poles and memorising the course to devise a plan.“

Although her skiing career was only four years, Gapes packed in a lifetime of memories, but says it’s not a sustainable path for many people with disabilities.

“People who are Paralympians cannot do it for that long because you need equipment, support crew and you need to earn an income. The effort is great, so they aren’t usually in it for that long,“ she says.

Gapes has been back involved in the Paralympic movement, volunteering her time to help Paralympics New Zealand make contact with past athletes for the Celebration Project.

The project honours our 209 Paralympians by presenting them with their unique athlete number.

“It’s been a real track and trace exercise; Jacinda should have me in charge of contact tracing,“ laughs Gapes.

There are now only seven people missing from the Paralympians list.

When Gapes spoke with athletes, she says they were “pretty chuffed“ to have their achievements recognised. Her search even unearthed an old ‘84 teammate, Paralympian #29 Craig Philip.

“I was excited to call and catch up. He’s married with two daughters, lives in Christchurch and still skis,“ she says. Their team of eight have met up a couple of times but they’re spread all over the world now.

The slightly “bold and nosey“ Gapes wanted to volunteer for the Tokyo Paralympic Games next year but then laughed and thought “What am I going to help with? I can’t see!“

“I just wanted to go because I love seeing them do well. And even when they don’t do well, I just love seeing the effort and striving for the best because you just learn so much through doing that alone,“ Gapes says.

Towards the end of her competitive career, Gapes started writing articles on skiing and completed a year-long journalism diploma at Wellington Polytech in 1986. The following year she retired from skiing – ending on a high with the New Zealand Skier of the Year award.

Gapes began working at the Blind Foundation, where she was one of the first to write much-needed brochures for the organisation.

She moved to Auckland 30 years ago, met her future husband, Rob, and had a family. Viv took on the full-time role of raising their kids.

“I’ve carried on skiing recreationally and we’ve passed that on to our kids,“ she says. “We’ve had wonderful family times because it’s an amazing sport in that everyone can take part.“

The children used to take their mother’s medals to school. “I’ve got loads of them. I have some from American regional races, and I think I won the American champs and the Canadian champs too,“ she says modestly.

She’s also kept all the pins and badges that were swapped with other competitors at international events.

“It’s pretty surreal because you almost forget about it, and then something will happen, like the 50 years of Paralympics in New Zealand event and you go ‘Oh yeah that’s right, I did that’,“ she says.

For Gapes, organising walks around the world with her three friends, nicknamed the Walkie Talkies, is now her adrenalin hit.

With lockdown restrictions over, the Walkie Talkies are planning their next adventure to Bream Head near Whangarei. Gapes and a group had to scramble – literally – through to finish the Hump Ridge Track in Fiordland just before New Zealand shut down.

“It’s really extreme, but it’s so gorgeous. We had to scramble vertically to get up to the top though,“ she says.

“I usually struggle coming down because the ground is going away from me, so I have walking poles for balance because my balance is shot.“

But like every challenge in her life, that isn’t going to deter Gapes from her adventures any time soon.