Story written by Suzanne McFadden for LockerRoom.

The search for our missing Paralympians has unearthed gold – the fascinating story of a Kiwi woman who won silver but came home with bronze.

There is nothing straightforward in the life of Heneti Morgan – the Paralympian who was lost, but now found.

From a roller skating girl on the Kapiti Coast, to the car crash in England which changed her life forever, to the generosity of a war hero, it’s an intriguing tale. Even the medal she came home with from the 1972 Paralympic Games comes with a twist.

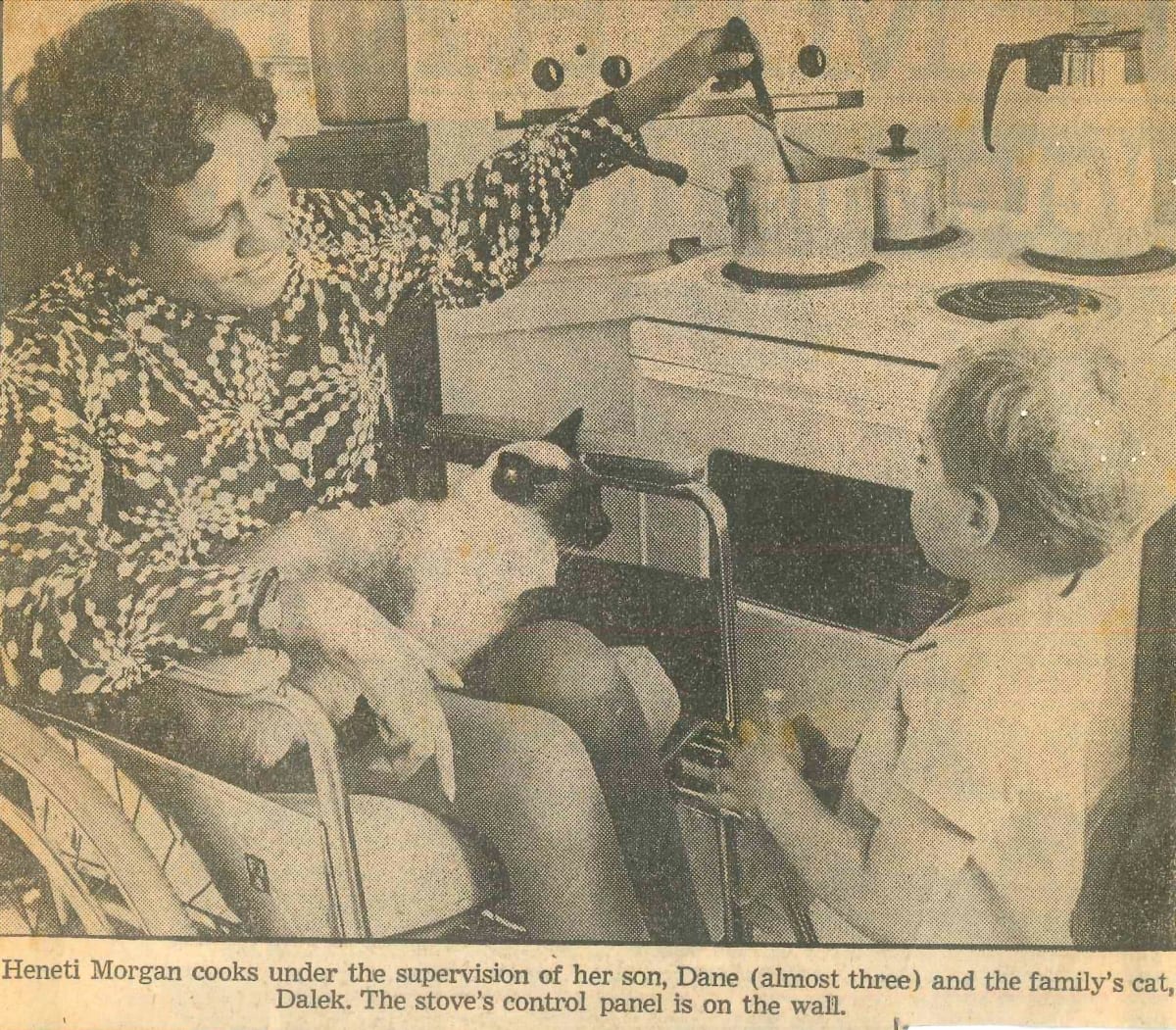

Dane Morgan treasures his late mother’s Paralympic bronze medal – but he knows it could have been silver.

His mum, Heneti (known to her sporting team-mates as Tina), represented New Zealand in six events at the 1972 Paralympic Games in Heidelberg, Germany, when Dane was only three.

In a wheelchair with tetraplegia after her car accident, Morgan brought home bronze from the pool, won in the 25m backstroke.

She had finished the race in second place and was presented with the silver – only to have to hand it back after an officials’ blunder.

“Technically, that bronze is a silver,“ says Morgan’s husband, Tony, who lives at Paraparaumu Beach. “But she had to keep schtum about it.“

Morgan passed away in 1987 at the age of 48, from complications after surgery on her spine.

She was one of 10 Paralympians at those Games in 1972, and she was New Zealand’s Paralympian #20.

But she was also one of 16 missing Paralympians – athletes that Paralympics New Zealand couldn’t track down for their ‘Celebration Project’, launched a year ago, to give all 209 of New Zealand’s Paralympic athletes a pin bearing their unique number.

Now her family has been found – after Dane heard about the search from a cousin. They will be presented with the pin at a special ceremony in Wellington, when it’s safe to hold such events again.

It’s a special way, her family says, to honour a woman remembered for her courage and tenacity, and for proudly representing her country at a Paralympic Games.

“What a thing for someone who couldn’t walk. Not only to be able to compete, but to travel that far,“ Dane says.

“Nothing swayed Mum. She was pretty determined and headstrong.“

Growing up on the Kapiti Coast, Doris Heneti Morgan was known to her friends as ‘Ti’.

“When she was playing up the creek as a kid, her grandmother would yell ‘Hene-TI!’“, husband Tony explains. The nickname was elongated to Tina when she was a tetraplegic athlete.

Morgan was on her OE in the Northern Hemisphere in 1960 when she was seriously injured in a car accident in England. She spent 11 months in the world-acclaimed spinal unit at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in Buckinghamshire, undergoing rehabilitation, before she was able to fly home to New Zealand accompanied by a nurse.

She rarely talked about the accident, says Tony, who met Heneti at a coffee bar a couple of years later.

Morgan took up Para sport 10 years after her accident. She had been a sporty kid – playing tennis, swimming and roller skating at the local rink.

She joined the Wellington Paraplegic Association, as it was known back then, and started by tossing a shot put and a discus. “She could throw them a fair way,“ Tony recalls.

At her first national championships in Hamilton, she defied doctor’s orders – competing only a few days after being discharged from hospital following surgery – and won five gold medals and a silver.

It was in the water that Morgan felt most at ease. And it was through the kindness of a World War 2 hero that she was able to relearn how to swim.

Alex McKimm was an English pilot, who landed a glider behind German lines on the Normandy Coast on D-Day in 1944. He later moved to New Zealand, launched a successful boat-building business in Paraparaumu, and had a 25m indoor heated pool built in his backyard for his daughters. He also opened up the pool to local swimmers, and took a special interest in Heneti Morgan’s progress.

“A district nurse arranged for her to swim in the pool, where she learned to float and then started swimming with her arms. She loved that she had her flotation again, that she could take all the weight off her body,“ Tony says.

McKimm would encourage her on the side of the pool, and within three years she could swim.

Among those impressed by Morgan’s athleticism and determination was Sir Ludwig Guttmann, the German-born English neurosurgeon who founded the Paralympic Games.

Guttmann had been in charge of the spinal unit at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, and believed the best way to rehabilitate patients with paraplegia was through sport. The competitions he held would grow into the Paralympic Games.

He remembered Morgan from her time in the spinal unit and stopped by to see her during a visit to New Zealand in 1971. “There he was, in our lounge,“ Tony remembers.

Photo: Kapiti Coast District Libraries/HP1594.

Morgan qualified for the 1972 Paralympic Games in Heidelberg when she was 32, and travelled to Europe with nine other Kiwi Para athletes and their escorts. Tony stayed home to take care of Dane, who the couple had adopted when he was five days old.

The New Zealand team included two other women. Eve Rimmer was the first Kiwi to win a Paralympic medal, at the 1968 Games – and would win four medals in Heidelberg. Neroli Fairhall was a young archer, who became the first Para athlete to win Commonwealth Games gold and the first to compete at an Olympics (in Los Angeles, 1984).

The travelling knocked Morgan around. A local newspaper reported that she suffered thrombosis (a blood clot) from the flying. “After training two hours a day, seven days a week since Easter, I hardly felt like stopping at that late stage,“ Morgan was quoted as saying.

So she went ahead and competed in six events, including table tennis, athletics and swimming. She finished fifth in the discus and sixth in javelin.

But it was in the pool where she really shone. While the records show Morgan won bronze in the 25m backstroke 1B classification, her husband says she should have won silver.

“She came second in the race. But after everyone dispersed, the Dutch team came over and said ‘you never called our swimmer for the race’. So she got to swim a time trial in a dead calm pool with no-one there in the evening. And she pipped Ti’s time.

“They took the bloody medal off her and gave her the bronze. The poor girl who won bronze got nothing. They were told not to protest, they had to go schtum on it.“

Regardless of the medal’s colour, Morgan’s family are incredibly proud of her achievements. Of the nine medals New Zealand won at those Games, Morgan’s was the only one won in swimming.

She kept competing for a few years – “but she was getting older and more tired,“ Tony says. The couple adopted a daughter, Rewa, too.

Late in 1986, Morgan went into hospital for surgery on her crumbling tail bone.

“Two weeks after that, it all went sour,“ says Tony. “The blood supply to her bowel had been cut off. The doctors and nurses at Hutt Hospital worked like hell to keep her alive.“ But she died after five months in hospital.

There have been seven Celebration Project events around the country to honour the athletes, with another four put on hold because of Covid-19.

Dane Morgan contacted Paralympics NZ on behalf of his family after a cousin saw Heneti’s photo on television. “He remembered her, and told me they were looking for the last 16,“ he says.

“We will all get along to the presentation in Wellington when it happens.“

Dane is the keeper of his mother’s medal, but she left so much more with him. There’s a newspaper photo of a two-year-old Dane ‘supervising’ as she cooks. “Now it’s what I do for a job,” the construction site supervisor says.